It's Time for Rights Restoration

America has a recent history of massive civil-rights

infringement of citizens' Second Amendment-protected rights

(Francis Chung/AP)

By Charles C. W. Cooke. July 24, 2025

Article Source

Under federal law, Americans who have been convicted of crimes that are punishable by prison sentences of more than one year's duration are automatically deprived of their constitutional right to keep and bear arms—even after their sentences have been completed and even if the person never actually served a day in custody. This rule has been in force since the passage of the 1968 Gun Control Act, and it is applied everywhere in the country, irrespective of the character of the crime at hand.

Outside of a few esoteric exemptions ("antitrust violations, unfair trade practices, restraints of trade or other similar offenses relating to the regulation of business practices"), and an asterisk next to state misdemeanors that yield imprisonment of two years or less, there are no caveats within the statute. The law does not distinguish between violent and nonviolent crimes; it does not turn upon a finding of dangerousness; and it includes no classification mechanism to sort between different types of lawbreaking. In consequence, it applies equally to a person who has been convicted of misdemeanor welfare fraud and is sentenced to probation as to a person who has been convicted of felony murder and serves decades in prison—providing that the sentencing guidelines fit the bill.

If, in a fit of overzealous pique, a state were to turn littering into a felony punishable by more than 365 days in prison, those who were convicted under that law would automatically lose their right to keep and bear arms. In this area, alas, the justice system isn't so much blind as it is braindead.

Putting to one side the asininity of the approach, there are two legal problems with this system that simply cannot be ignored. The first problem is that the disqualification parameters written into the 1968 Gun Control Act are plainly unconstitutional—and have become especially so in light of the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen (2022), which required that all firearms laws must have a clear historical analog or be presumed invalid. The second problem is that, thanks to a cynical change that was made in 1992, Congress has foreclosed the only avenue for appeal that had been made available to the citizenry. When combined, these two decisions have resulted in a core civil right being routinely infringed, and in nobody—however deserving—being able to seek a reprieve.

Until now. In April, the Trump administration processed the first Second Amendment-restoration cases for individual applicants in more than three decades, and, in so doing, signaled that the era of perennial punishment was coming to an end. Announcing the move, Attorney General Pam Bondi submitted that she had "established to her satisfaction that each individual" whose application she had accepted would "not be likely to act in a manner dangerous to public safety, and that the granting of the relief to each individual would not be contrary to the public interest." Among those covered by the order were the actor Mel Gibson and NFL Hall of Famer Joseph Klecko. Astonishingly, despite this mechanism being a key component of the country's criminal law, and there being tens of thousands of Americans who qualify to apply, Bondi's decision marked the first time in 33 years that the recovery process had been used.

How We Got Here

The road to this restoration was long, complicated and often downright disgraceful. In 1968, Congress passed the Gun Control Act, which, for the first time in American history, created a sweeping federal ban on gun ownership for a whole host of convicted criminals. In the same law, Congress stipulated that "a person who is prohibited from possessing firearms may apply to the Secretary of the Treasury for relief, and the Secretary may grant such relief," providing that doing so was not contrary to the public interest. A year later, in 1969, the Secretary of the Treasury issued a directive delegating the authority to restore eligible felons' gun rights to what was then known as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), which, for 23 years, the ATF did.

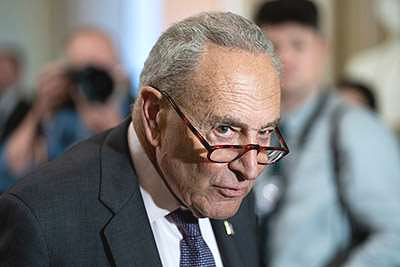

But in 1992, Congress passed a rider (written by then-U.S. Rep. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.)) that flatly forbade the ATF from using federal funds for the restoration of Second Amendment rights—this, in effect, shut down the appeals system completely.

In 1992, Congress passed a rider (written by then-U.S. Rep.

Chuck Schumer) that forbade the ATF from using federal

funds to restore citizens' Second Amendment-protected

rights. (Bill Clark/AP)

That rider is still on the books. But, crucially, it applies only to the ATF, which is not named in the 1968 Gun Control Act, but is merely the temporary recipient of a delegation by the cabinet official that is. In 1968, the power to restore gun rights was granted to "the Secretary of the Treasury."

In 2002, however, in the wake of the September 11 attacks, Congress explicitly transferred oversight of ATF to "the Attorney General" of the United States—who, at present, is Pam Bondi.

What is Happening Now

In one of her first moves after taking office, Bondi reversed the 1969 rule that had delegated the restorative authority to the ATF, reclaimed the power that Congress had accorded her office and set about revivifying the appeals system that Sen. Chuck Schumer (D) helped to kill all those years ago.

It is unlikely that Bondi will remain personally responsible for each application. But, by salvaging the control that Congress unequivocally vested in her department, she has created a salutary new status quo. For now, Bondi will be able to address pressing demands for relief, while working on a new set of rules, guidelines and standards—and, eventually, finding a different DOJ component to take on the work.

This process will no doubt be demagogued by the opponents of the Second Amendment. But it is those who destroyed this check and balance, not those who have saved it, who merit our opprobrium. In 1968, Congress created a safety valve for its sweeping new law—a valve that, scandalously, has been completely closed for more than 30 years. At long last, it is open again.

Naturally, this change represents a substantial improvement. But it does not address the key problem with the felony-restriction provisions of the 1968 law—which is that they are obviously overbroad. As the Supreme Court's Bruen decision confirmed, all laws relating to guns must sit within the United States' "historical tradition of firearm regulation." Prohibiting convicted criminals from owning firearms without reference to the category of crime quite obviously does not fall within that "historical tradition." Indeed, even if one broadens one's scope of inquiry beyond all reason and searches for the vaguest of vague equivalents, one will still uncover nothing that fits the bill.

Among the behaviors that have, at various points in America's past, yielded government action that limited the keeping and bearing of arms are rioting, dueling, wartime disloyalty, the willful causing of "an affray" or a judicial finding of "dangerousness." Some of these measures were sensible, while others were pretextual, but none can be reasonably used to justify the existence of a law that, since its passage, has been used to void the Second Amendment rights of figures who have been convicted of crimes such as welfare fraud, tax evasion, insider trading, lying on a mortgage application, the possession of marijuana or the violation of the Clean Water Act.

Some of those may, indeed, be serious crimes that warrant serious punishment. But, until the mid-20th century, it had occurred to nobody that a part of that punishment should be the categorical lifetime loss of a core constitutional right.

The Legal Fight Ahead

In 1968, the federal government transmuted the historical precedents' temporary responses to dangerous conduct into a permanent consequence for all (what the state considers) major lawbreaking. This decision cannot be squared with our Constitution.

The good news is that, in some recent litigation, it has not been. In 2023, in Range v. Attorney General, for example, the Third Circuit held that a man who had been convicted for making a false statement to obtain food stamps (a misdemeanor in Pennsylvania) could not legitimately be deprived of his Second Amendment rights. In the majority opinion, the court concluded that "the Government [had] not shown our Republic has a longstanding history and tradition of depriving people like Range of their firearms," that the "record contain[ed] no evidence that Range poses a physical danger to others" and that, in consequence, the portion of the Gun Control Act that had been used to disarm him was unconstitutional as applied to his case.

The bad news is that, in other litigation, other courts have found the opposite. In the same year as Range was issued, the Eighth Circuit upheld a lifetime ban against a Minnesota man who had been convicted of selling controlled substances on the highly questionable grounds that American "legislatures traditionally possessed discretion to disqualify categories of people from possessing firearms to address a danger of misuse by those who deviated from legal norms, not merely to address a person's demonstrated propensity for violence."

The not-quite-sure-yet news is that the Fifth Circuit and the Seventh Circuit have also grappled with this issue, and both have produced ambiguous or incomplete results. This uncertainty is bad for the stability of the law, and it makes a mockery of a right that is supposed to be universal. (At present, nonviolent felons in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware are allowed to own firearms, while similar individuals in Missouri, Arkansas and Minnesota are not.) At the same time, the turmoil makes it more likely that the Supreme Court will feel obliged to step in and resolve the matter once and for all.

It is, of course, impossible to know definitively what such a resolution would look like, were it to come. But, if the recent (post-Bruen) Rahimi case is any indication, the Court may well determine that only the violent or dangerous among the country's convicted criminals may be disarmed. In Rahimi, the Supreme Court's majority opinion held that the nation's "tradition of firearm regulation allows the Government to disarm individuals who present a credible threat to the physical safety of others," that, "when an individual poses a clear threat of physical violence to another, the threatening individual may be disarmed" and that "an individual found by a court to pose a credible threat to the physical safety of another may be temporarily disarmed consistent with the Second Amendment." None of these precepts encompass nonviolent criminals.

Indeed, in both the judicial branch and in the executive branch, we are seeing more progress on this issue than at any point in the last 57 years. Prior to the Bruen decision in 2022, America's judges had no framework within which to properly evaluate whether the right to arms could be permanently suspended for millions of nonviolent Americans.

Prior to the Trump administration's decision to wrest responsibility for the restoration procedure away from the faceless bureaucracy, none of those Americans was able to file an appeal.

For decades, the only plausible avenue for a citizen who wished to reverse his lifetime federal ban on the right to keep and bear arms was a presidential pardon, which is vanishingly rare.

Today, many such citizens might have a reasonable chance in the courts, and an ever-increasing shot at entering into a federal procedure that could generate relief.

It is true, indeed, that a right delayed is a right denied. But it matters enormously on which side of the equation each political player finds himself.

Pam Bondi, along with the Supreme Court majority that wrote Bruen, have struck blows for the integrity of the Constitution. Hopefully, before long, the bells will ring out for nonviolent citizens who have been disenfranchised because of a bad check or some other minor offense.

![]()