The Lone Ranger Had Good Life

Lessons But Bad Gun Advice

By Cary Kozberg. July 21, 2023

Article Source

Like my male contemporaries growing up in the 1950s, I watched TV Westerns. Of all the cowboy heroes I followed, my favorite was The Lone Ranger. To this day, there are moments when listening to The William Tell Overture (TLR’s theme song) will deliver a quick uplift. Inevitably (and unashamedly), I will shout “Hi-yo Silver!” and continue reciting (in my best announcer’s voice) the opening monologue:

With his faithful Indian companion, Tonto, the daring and resourceful masked rider of the plains led the fight for law and order in the early West. Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear…THE LONE RANGER RIDES AGAIN!”

The TV cowboy heroes of the 1950s were heroes because they were exemplars par excellence of “the Good Guy”—knowing Right from Wrong, seeking to preserve Justice and Goodness, and always willing to help those who needed help. Today we call such individuals “sheepdogs.” The code of a true “sheepdog” is accurately reflected in “The Lone Ranger’s Creed”:

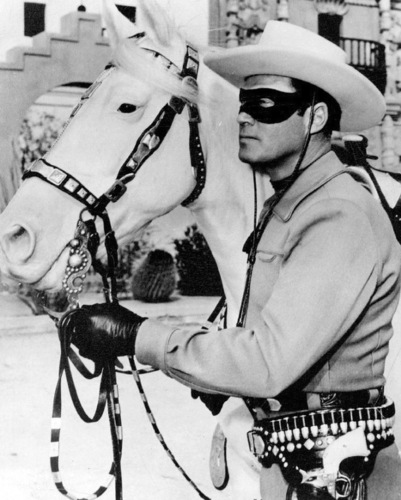

Image: Actor Clayton Moore as the Lone Ranger. Public domain.

I believe...

That to have a friend, a man must be one.

That all men are created equal and that everyone has within himself the power to make this a better world.

That G-d put the firewood there but that every man must gather and light it himself.

In being prepared physically, mentally, and morally to fight when necessary for that which is right.

That a man should make the most of what equipment he has.

That ‘This government, of the people, by the people and for the people’ shall live always.

That men should live by the rule of what is best for the greatest number.

That sooner or later ... somewhere ... somehow ... we must settle with the world and make payment for what we have taken.

That all things change but truth, and that truth alone, lives on forever.

In my Creator, my country, my fellow man.

As quaint as these tenets may sound today, they were axiomatic truths to TV cowboy heroes. I certainly took them to heart: Although I played with toy guns as a kid, I didn’t become a mass killer. Au contraire. I became a rabbi who has devoted my life to teaching folks the tenets reflected in this “quaint” creed. And, because the world is still unredeemed, I also advocate for the necessary (and responsible!) use of firearms.

Recently, in a moment of nostalgia, I decided to “return to those thrilling days of yesteryear” and watched the first episode of The Lone Ranger TV series. That first episode tells the story of John Reid, the Texas Ranger who was the lone survivor of an ambush by the Butch Cavendish gang. He is discovered by Tonto, who nurses him back to health and gives him the famous name Keemo Sahbee, which supposedly means “trusted friend.” In a dramatic moment after donning his iconic mask, Reid rededicates himself to bringing outlaws to justice. Pledging to do this, he nobly declares that he will never intend to kill, only to wound.

Until recently, I also believed it was morally preferable to intend to wound an armed “bad guy,” and then let the law decide his fate. Indeed, most people who believe in the sanctity of life probably would agree that it’s best to stop a threat by shooting the bad guy in the arm or the leg. And, I would add, after watching TV cowboys easily shoot guns out of bad guys’ hands, which appears to be eminently doable, so why intend to kill them?

But I’ve learned a bit more about handguns, Keemo Sahbee, and I must respectfully disagree with your noble statement, if only because, in real life, guns don’t function in the way TV and movies portray them:

- On-screen guns rarely, if ever, recoil, making it much easier to shoot the gun out of a bad guy’s hand, especially with only one hand. Real-life guns, however, always recoil and shooting a handgun with one hand makes the recoil even harder to control. The smaller the gun and the larger the bullet caliber, the more control is needed.

- On-screen, when the good guy fires his/her gun and wounds the bad guy, the fight is usually over. In real life, wounding one’s adversary does not automatically stop his/her ability to keep fighting, especially if his/her shooting hand is still functional. Therefore, it’s imperative that the defender keep firing until the threat of harm is neutralized.

- Keemo Sahbee, your TV heroes were always quicker on the draw than the bad guys you fought. You could shoot accurately from the hip, again with little recoil management or sight acquisition needed. After a gunfight, you would twirl your guns back into their holsters. As cool as this always looked, it should never be tried “at home”! Why? Because it requires that a finger be inside the trigger guard—a big NO-NO! Proper re-holstering requires 1) checking one’s environment for any other potential threats and 2) carefully guiding the gun(s) back in their holsters. These last two steps are basic and necessary actions that every beginning shooter learns.

Again, with respect, Keemo Sahbee, we don’t live in TV cowboy land. We live in the real world, which means that firearms must not be handled as cavalierly as you TV heroes were able to do on screen. In our real world, they must be handled and used with the utmost caution and responsibility. In our real world, they must be used only as a last resort when another individual threatens life and serious bodily harm. If we conclude that the situation has reached that point, That said, our intention must always be to do whatever is necessary to stop the threat. If the bad guy is merely wounded when we’ve neutralized the threat, so much the better. If the threat is stopped because it was necessary to take the bad guy’s life, we should feel regret…but not guilt.

Keemo Sahbee, in your world, shooting to wound was a noble approach. It reflects your creed’s affirmation of the sanctity of life. However, in our world, there are times when affirming the sanctity of life may require taking the life that threatens that sanctity. When we use a firearm with the requisite skill and with deep regret, we trust that we continue to follow in your footsteps—working to make this world into a place in which the services of you and all sheepdogs will no longer be needed. We hope and pray that that time comes soon.

When it does, the thrill that came from returning to those days of “yester-year” will be surpassed by the thrill of living in a world that you TV heroes worked to achieve.

(First published in The American Thinker, 7/21/23. Used with permission.)

![]()